On April 24, 2015, we (D. Benjamin Sessions, Robert Chestney and I) were excited to meet with Georgia Public Defenders at the State Bar to discuss the new Georgia Supreme Court decision Williams v. State, ___ Ga. ___ (Case No. S14A1625, decided 3/27/15) and how it affects any state-administered test submitted to pursuant to implied consent.

In March of 2015, the Georgia Supreme Court held that a trial court must determine whether a police officer’s request for a blood sample from a driver who has been arrested for DUI complies with the protections afforded by the Fourth Amendment.

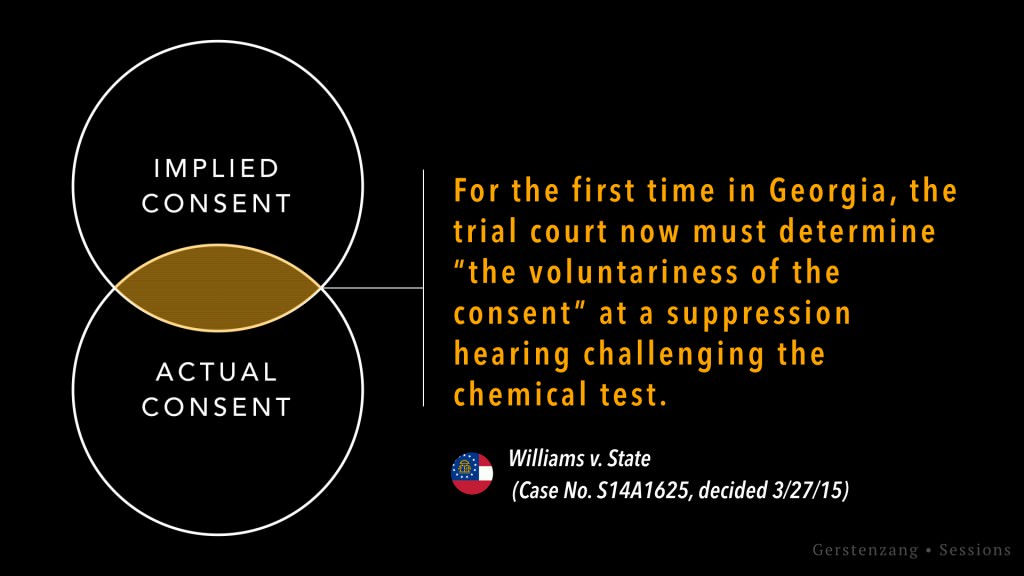

In Williams, the Supreme Court distinguished between “implied consent” under OCGA § 40-5-55 and “actual consent” which is required to permit a warrantless search. Under Williams, the trial court must determine whether actual consent was given, “which would require the determination of the voluntariness of the consent under the totality of the circumstances.” Williams v. State, ___ Ga. ___ (Case No. S14A1625, decided 3/27/15).

For 49 years prior to Missouri v. McNeely, 133 S. Ct. 1552 (2013), the legal community was under the impression that Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966) had established a “DUI Exception” to the Fourth Amendment. In 1966, the Schmerber decision held that because there was evidence of a crime in the defendant’s blood (alcohol), and that evidence was rapidly dissipating, this type of warrantless search would be permitted under the exigency exception to the Fourth Amendment. In 2013 however, the McNeely opinion explicitly corrected that misinterpretation of Schmerber, advising that there is no such per se rule regarding blood testing and exigency, but that rather each case must be decided on a case-by-case basis.

At the outset, the first question to be addressed is whether the Williams and McNeely holdings apply to breath testing, since both of those cases involved a blood test. Happily the US Supreme Court resolved this issue for us more than 25 years ago in Skinner v. Ry. Labor Executives’ Ass’n, 489 U.S. 602, 616-617 (1989). Skinner held that a breath test “implicates similar concerns about bodily integrity and . . . should also be deemed a search.” Skinner v. Ry. Labor Executives’ Ass’n, 489 U.S. 602, 616-617 (1989).

Under Williams the trial court must determine voluntariness of the consent under the Fourth Amendment. But before we can get to that question, first we have to get past the threshold inquiry of whether the driver even consented to the breath/blood test. Consent is almost never requested under the Georgia implied consent regime. Drivers are not asked if they will consent to a search and test of their bodily substances – they are asked, “will you submit [to the testing] under the implied consent law?” Webster’s defines the intransitive verb “submit” as follows: “to yield oneself to the power or authority of another.” Legally speaking, “submission” means “[a] yielding to the authority or will of another.

The statement, “Georgia law requires you to submit to [testing]” is false. No law in Georgia requires a person to submit to the test. Georgia has no criminal statute making it illegal to refuse testing. Compare the Minnesota Supreme Court decision in State v. Brooks, 838 N.W.2d 563 (Minn. 2013). There, the advisement given “informs drivers that Minnesota law requires them to take a chemical test . . .” But in Minnesota, that statement is true – “It is a crime for a person to refuse to take a test required under the implied consent law.

The recent out-of-state cases addressing McNeely are not appropriately applied for the purposes of resolving the Fourth Amendment concerns here in Georgia. In Minnesota, drivers are advised that they have the right to speak with an attorney prior to deciding whether to consent to a test, whereas in Georgia, drivers have no such right. State v. Brooks, 838 N.W.2d 563 (2013).

In Wisconsin the implied consent advisement makes no mention of drivers being required to submit to chemical testing. Rather, Wisconsin drivers are simply notified that the officer would like to test their breath or blood and what the consequences would be should he/she refuse. State v. Padley, 2014 WI App 65,1, 354 Wis. 2d 545.

In Wisconsin the implied consent advisement makes no mention of drivers being required to submit to chemical testing. Rather, Wisconsin drivers are simply notified that the officer would like to test their breath or blood and what the consequences would be should he/she refuse. State v. Padley, 2014 WI App 65,1, 354 Wis. 2d 545.

The Williams decision did not adopt California’s perfunctory analysis of actual consent in People v. Harris, 234 Cal. App. 4th 671, review filed (Apr. 2, 2015). But rather, Williams remanded the case to the trial court for a more meaningful Fourth Amendment analysis. By contrast, the Harris opinion seems to suggest a shifting of the burden to the defendant to provide evidence that the consent was involuntary when it held that the lack of evidence that defendant was reluctant to submit was sufficient to support a finding that the defendant actually consented to testing.

The Williams decision did not adopt California’s perfunctory analysis of actual consent in People v. Harris, 234 Cal. App. 4th 671, review filed (Apr. 2, 2015). But rather, Williams remanded the case to the trial court for a more meaningful Fourth Amendment analysis. By contrast, the Harris opinion seems to suggest a shifting of the burden to the defendant to provide evidence that the consent was involuntary when it held that the lack of evidence that defendant was reluctant to submit was sufficient to support a finding that the defendant actually consented to testing.

[T]he record demonstrates that defendant verbally agreed to a blood test after being admonished by Deputy Robinson under the implied consent law, and that he did not verbally refuse to give a blood sample or demonstrate a desire to withdraw his consent either verbally or by physically resisting the phlebotomist’s attempt to draw his blood

People v. Harris, 234 Cal. App. 4th 671, 690, 184 Cal. Rptr. 3d 198, 214 (2015), review filed (Apr. 2, 2015).

Unlike the discussion in Harris, Williams reminds us that mere acquiescence to the authority asserted by a police officer cannot substitute for free consent.

In Garrity v. New Jersey, the US Supreme Court made clear that, just as Odysseus did not have a “free choice” when faced with the option of steering his ship towards a treacherous whirlpool or risk being tossed against the rocks by the sea, a decision made under duress is not a free choice under the Fourth Amendment. The Garrity opinion is tremendously instructive here, particularly when the government attempts to rely on the convenient, but not necessarily relevant passage from Harris: “the choice to submit or refuse to take a chemical test ‘will not be an easy or pleasant one for a suspect to make,’the criminal process’ often requires suspects and defendants to make difficult choices.” People v. Harris, 234 Cal. App. 4th 671, 687 (2015), review filed (Apr. 2, 2015).